-

EBITDA – The elephant in the cloud, and in AI

Public cloud offers to swap upfront capital investments with consumption based pricing for infrastructure spending. This has 2 obvious consequences:

1. Reduce infrastructure costs by optimising consumption and right sizing the infrastructure estate.

2. Make technology cashflows more granular and on-demand enabling start-ups and scale-ups to compete with enterprises.

The 3rd less obvious consequence is the impact on the perceived financial performance of a firm. Most established businesses use EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation) to report their financial performance. Its appeal is its simple calculation despite it not being an acceptable metric for financial performance under GAAP (Generally Acceptable Accounting Principles).

EBITDA ignores the capital expenditure (CapEx) but accounts for operating expenses (OpEx). Spending on on-premises infrastructure is considered CapEx while cloud costs are considered OpEx. As the infrastructure CapEx transitions to cloud OpEx, it decreases the firm’s EBITDA. This creates the perception of poor financial performance.

Increased cloud spending with AI is further compressing operating margins and stressing EBITDA. This creates tension within a firm due to increased OpEx, especially before the commercial benefits from AI are realised, just like in cloud adoption. Prematurely and speculatively cutting costs tends to stifle innovation which may increase EBITDA in the short term. But stalled innovation and lower than expected commercial benefits show only marginal improvements in EBITDA subsequently.

The purpose of this blog is to introduce this key financial metric to technology leaders and how their technical decisions impact the perceived financial performance of their firms as a set of FAQs.

- So, what is EBITDA?

- Why does it matter to the public cloud and AI?

- What reduces the impact on EBITDA when migrating to public cloud and adopting AI?

- How to practically avoid impacting EBITDA?

- The middle ground – how cloud and AI costs can be capitalised?

So, what is EBITDA?

EBITDA represents a company’s cash profits generated by its operations. It is a widely used measure of corporate profitability to net income despite not being recognised by GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles).

EBITDA is calculated as follows:

EBITDA = Net income + Interest + Tax + Depreciation + Amortisation

Hence it excludes capital expenditure but includes operating expenses.

EBITDA is largely used in the analysis of asset intensive companies that own a lot of equipment and thus have non-cash depreciation costs, but the costs it excludes may obscure the underlying profitability.

Why does it matter to the public cloud and to AI?

Public cloud’s usage based pricing is regarded as an operating expense, hence it reduces the net income which is not discounted as CapEx is, thereby reducing the EBITDA. On premises infrastructure incurs a capital expenditure which depreciates in value thereby not affecting the EBITDA.

Most firms use AI models hosted on public cloud, which means an increase in their operating expenses for executing tasks that rely on AI. AI promises to provide operational efficiencies that may reduce the operating expenses in the medium to long term. But the increased cloud consumption because of AI may lower EBITDA in the short term and may also eat into the savings due to operational efficiencies eventually gained from AI.

Therefore, firms reporting their financial performance in EBITDA, may report lower profitability when migrating to and operating on public cloud and using AI on public cloud.

This may lead to an overbearing and regressive focus on cloud and AI cost control.

What reduces the impact on EBITDA when migrating to public cloud and adopting AI?

Public cloud has higher unit cost as compared to on-premises infrastructure. A like-for-like setup on public cloud will invariably be more expensive with costs effectively reducing EBITDA. Cloud provides opportunities for efficiency and economy as well as innovation and growth that can reverse the impact on EBITDA, let alone lower it.

This requires addressing OpEx both on cloud and on-premises. As cloud usage increases and the on-premises footprint reduces, there are opportunities to also progressively lower operating expenses on-premises.

Frequent cloud usage optimisations help avoid unnecessary cloud OpEx. This is not a substitute for negotiating and contracting favourable cloud usage rates. While a team may focus on both, usage optimisations can yield continuous efficiency and economy on public cloud.

It is important to remember that cloud costs will increase as business volumes scale. Cloud usage optimisations should also consider unit economics as an indicator to the impact on EBITDA with increasing costs. Unit economics refer to costs per unit of business activity and it should not be confused with unit costs. Examples of unit economics include cost per million transactions or cost per million active users. While costs increase with more transactions or customers, so does the revenue. But if the unit economics remain constant, EBITDA may not reduce because of increasing cloud costs.

A balanced and disciplined approach to adopting AI can help reduce the impact on EBITDA. AI without hygiene in technology and data will invariably increase costs without providing the expected returns. Furthermore AI should be reserved for tasks most suited for it in a hybrid ecosystem of AI and conventional services that are orchestrated together to deliver the desired results.

How to practically avoid impacting EBITDA?

Avoid a big bang lift and shift involving long testing cycles and suboptimal cloud usage. Instead incrementally migrate capabilities to the public cloud and decommission them on-premises when they are in production in the cloud. Decommission capabilities that provide diminishing returns on-premises to reduce cloud usage. Optimise for base load and horizontally scale for increased load.

Rightsize resources allocated in the cloud. This also means only provisioning enough resources when incrementally migrating instead of the entire infrastructure footprint at par with on-premises infrastructure. Understand and exploit the duty cycle of non-production environments to release them when they are not needed.

Improve the quality of data which will lead to improved context with fewer tokens and more efficient processing by the LLMs. Further, agents that use conventional processing tools (business domain services, e.g., pricing calculators etc.) with LLMs also optimise processing. All of these help optimise AI usage.

Last but not least, consider opportunities to increase revenues on cloud, e.g., monetise data and value added services.

The middle ground – how cloud and AI costs can be capitalised?

Some firms are looking to account for cloud and AI operating costs as CapEx. This may (superficially) reduce the impact on EBITDA but may also reverse the cost savings that a firm wishes to achieve when using public cloud.

For costs to be regarded as CapEx, they need to be assessed and budgeted up front in annual budgeting cycles and not realised on the go. This will drive the same on-premises behaviour which leads to over provisioning and waste on cloud.

This may also lead to regressive controls on cloud provisioning and AI use, even when that usage clearly demonstrates a substantial upside for the business, just because that usage exceeds the annual budget.

Having said that, there may be opportunities to capitalise long term reservation and committed usage contracts. Care must be exercised to not restrict or constrain the on-demand usage exceeding these contracts to take advantage of emerging business opportunities.

Here, amortised long term cloud and AI reservations and committed usage costs are not reflected in the EBITDA but those exceeding these contracts are.

The FinOps function here needs to be firm that such contracts are made to minimise overall cloud and AI costs instead of optimising the EBITDA. This will ensure a focus on optimising costs and unit economics instead of one on just the perceived financial performance of the firm.

-

Cloud is not expensive – our habits are

Most enterprises can save up to 40% of what they are currently spending on public cloud

Cloud largely charges for provisioning, not utilisation – a fine detail that many forget, leading to escalating wasted spend on public cloud. So it is not surprising that a 2025 study finds that nearly a third of businesses waste over 50% of their cloud spend due to under utilised resources.

While most businesses have mastered self service on cloud to scale and accelerate time to market, the same cannot be said for achieving the transparency to analyse, consolidate and economise their cloud spend.

Lack of situational awareness on cloud can be embarrassing for technology leaders. It may even hurt their personal career and growth perspectives as fiscal control and responsibility starts becoming a part of their KPIs. Building that transparency requires consolidating data from multiple sources. This should be front and center to cloud enablement as part of the cloud operating model, right besides technology skills and practices.

With cloud costs under a spotlight across the industry, FinOps and cloud costs management cannot be an afterthought. Focusing simply on contract negotiations to earn cloud discounts may only yield temporary relief. Once these discounts run out, further painful negotiations may be needed to avoid shocking price hikes.

Identifying and exploiting opportunities to right size environments, making them ephemeral and only provisioning them when required can bring substantial cloud economy. This requires both a culture that inculcates fiscal discipline across the organisation, and continuously improving technology and practices to surface and remove wasted cloud resources.

Taking only what you need

If your cloud bill is higher than your on-prem costs for the same infrastructure footprint, you could be saving up to 40% of what you actually pay!

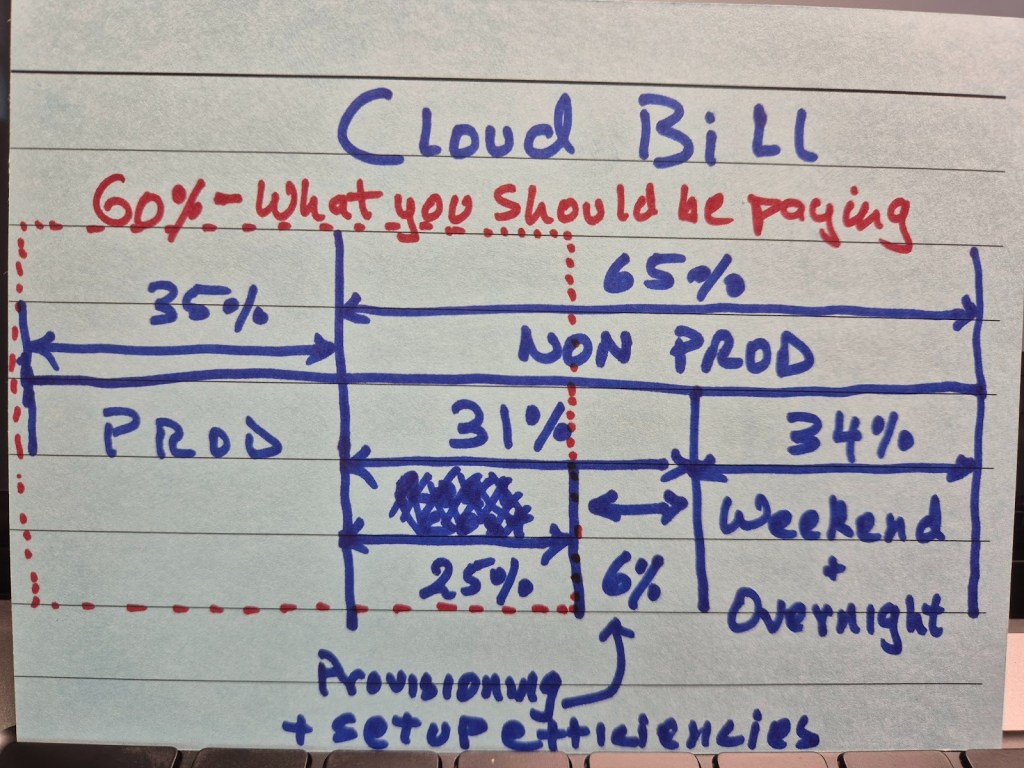

Here’s what we worked out in a couple of hours of brainstorming – this may vary based on your circumstances but simple efficiencies can create real differences.

Think about your non-production environments. Typically your non-prod footprint will be at least twice the size, if not thrice, of your prod footprint. This means you may be spending twice as much on your non-prod environments, around 65% of your cloud bill.

But if you can make your environments ephemeral, you can spin them down overnight and on weekends (and public holidays). That should take away 34% of your cloud bill, if not more.

Then think about the duty cycle of your automated testing cycle – what proportion of your time do you spend testing vs preparing environments, deploying software and setting up test data? The longer it takes you to do all this set up, the longer your non-production environments are provisioned on cloud but are not doing anything meaningful.

Some estimates suggest teams spend up to 40% of their QA time in these preparations. Here we just took a nominal 6% saving with efficiencies in provisioning, deployment and data hydration. In many cases, this can be much higher.

There can be further non-prod savings, making your testing more efficient and reliable which would reduce your load on non-production environments giving you opportunities for further savings.

Levelling up with the business

From the very beginning, technology should try to get business and finance to expand the conversation from just cloud costs to include unit economics and margins. Unit economics focus on cost per unit of a business activity, for instance, cost per hundred thousand customers or cost per million transactions. This brings cloud costs in the perspective of business activity.

With an agreement on suitable unit economics metrics, technology can optimise systems to unit economics baseline. From there, any cloud cost increase should be seen in conjunction with the baselined unit economics. If unit economics metrics remain within tolerance limits of the established baselines, these higher costs are due to increased business volumes which should translate to higher revenues.

Once this level of maturity has been achieved, business and technology will work together to leverage cloud as a business enabler. Especially if systems have been decoupled and modularised to reduce scale-up costs, it will increase the extensibility and flexibility of the systems to provide business the agility it needs to pursue emerging market opportunities.

Going further with cost savings

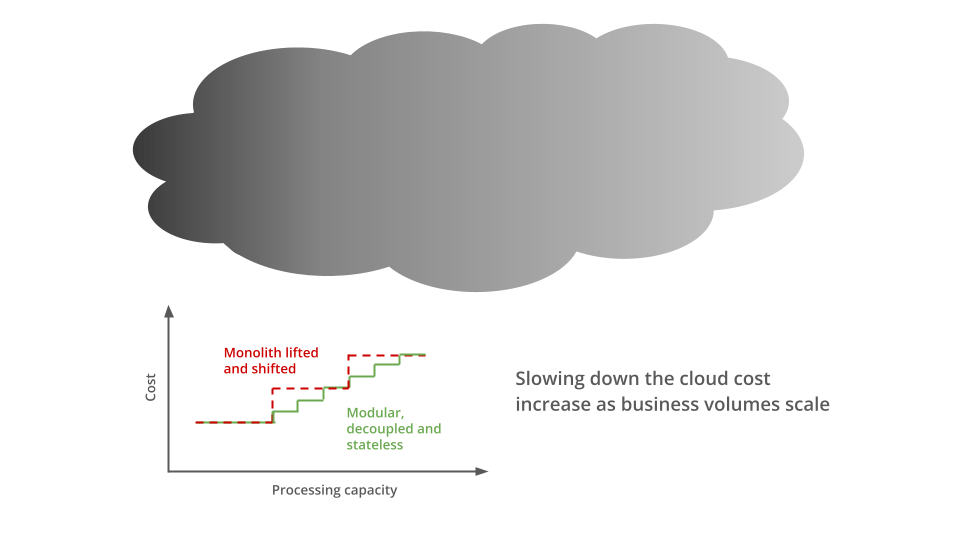

Your cloud costs are bound to grow as your business scales. With an increasing number of customers and transactions, resource requirements for your applications will also increase, leading to higher costs. The challenge is how to keep the scale-up costs low and incremental. If these applications are monolithic and tightly coupled, scale-up costs can be high with potential wastage of infrastructure. Reducing scale-up costs and making them incremental requires modularising and decoupling your applications. Then only the bottlenecked services need to scale keeping costs and wastage low.

Modularising and decoupling monolithic systems into cloud-native services can be expensive and risky. Businesses may need to be convinced to invest in such modernisation with a compelling business case showing a strong ROI and payback.

Further, a complete modularisation may not be necessary to start with, perhaps only the business capabilities and services that process varying transaction volumes and those that change often. The remaining can be retained within the monolith. This may help the organisation gain further confidence on the path to improved cloud economics.

But a partial modernisation carries the risk of a fragmented technology estate and a bimodal IT organisation. If not managed intentionally, they can increase both costs and risks to the business. This usually involves continuously improving and optimising to reduce friction and increase confidence in delivering value to business, which may mean going further with modularisation and decoupling, if required, and adapting the engineering operating model to manage dependencies between teams.

-

Scale out or sell out – How to tame your raging cloud bill

-

Scale out or sell out – How to tame your raging cloud bill

Scale-out costs

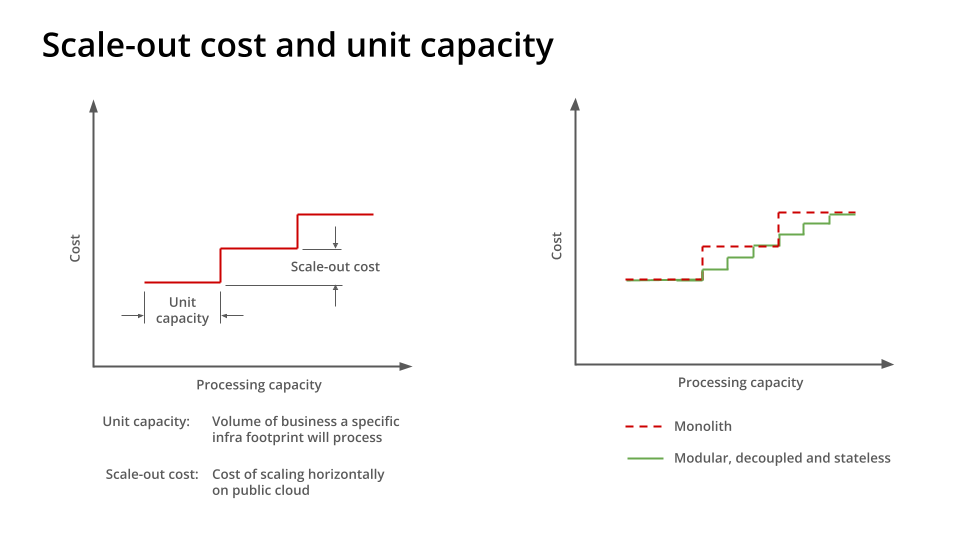

The costs incurred when scaling horizontally on a public cloud are referred to as scale-out costs. The more granular this scaling is, the lower are scale-out costs, giving firms higher margins when operating on public cloud.

Scale-out costs go hand in hand with a system’s unit capacity, i.e., the volume of business activity a particular infrastructure footprint will process before additional capacity needs to be provisioned to accommodate further volumes.

The knowledge of unit capacity and scale-out costs also help build rich unit economics models that enable technology to have meaningful cost conversations with the business in the context of business volumes and revenues. They also enable the technology to determine and optimise cost hotspots, i.e., the services where cost variations do not favourably align with business load variations.

Horizontal scaling on an elastic infrastructure was a key cost reduction measure that hyperscalars promised when promoting public cloud. Many argue that the manner in which public cloud adoption was pushed, with rushed migrations, firms were not given a chance to optimise for horizontal scaling and leverage granular scale-out costs. This has led to a perception of unfulfilled promises.

With this knowledge, what do we need to do minimise scale-out costs and increase the public cloud’s viability for businesses with rapidly and widely varying business activity.

In a nutshell,

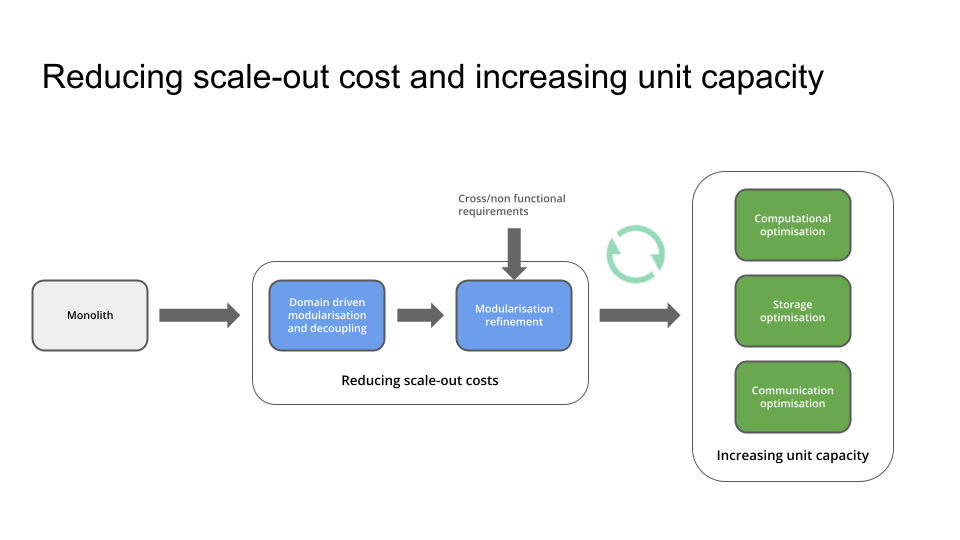

- it starts with modularising and decoupling a monolith along domain boundaries,

- further refining the granularity to meet specific scaling and performance requirements,

- optimising services for computational, storage and communication efficiencies,

- and continuously monitoring and optimising services to efficiently and economically scale according to business needs.

The cloud cost betrayal

One of public cloud’s big promises was cost reduction. But for most businesses adopting cloud, that has not happened. In fact, for many businesses, costs escalated to levels that forced them to repatriate some or all of their workloads back on-premises. Some reports suggest that if the AI workloads are discounted from hyperscalers’ revenues, their growth has declined to alarming levels.

One of the key reasons for high cloud costs was lifting and shifting on-premises applications to cloud without modularising, decoupling and optimising them. These applications over provision infrastructure footprints on cloud similar to that in the data centers. As infrastructure unit costs in public cloud are considerably higher than on premises, this leads to substantially higher operating costs in public cloud.

One other promise the public cloud makes is that of elastic capacity. This means that if an application on a public cloud experiences higher utilisation then it can be horizontally scaled (or scaled out) to balance the load and avoid impacting system performance and customer experience. Once the load on the application returns to normal, the application scales back in.

If an application is a monolith, coarsely modular or tightly coupled, it consumes greater incremental resources when scaling out, leading to higher scale-out costs. This is because the entire estate may need to be scaled out for higher loads. But if an application is composed of modular and decoupled services, only the services experiencing bottlenecks because of increased load scale out, thus reducing the scale-out cost for the application.Granularity – reducing scale-out costs

Modularity is just not enough to make scale-out costs granular. Only when modular services are decoupled and stateless, bottlenecked services can be scaled out independently thus reducing the scale-out costs.

A typical approach to achieving modularity and decoupling starts with identifying domain boundaries. The monolith can then be split along those domain boundaries into bounded contexts of one or more microservices. Further decomposition may be necessary to achieve specific cross/non functional requirements. For instance, if read and write loads on a particular microservice are asymmetric, that microservice may further be decomposed using the CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation) pattern. Such approaches may further reduce scale-out costs.

Statelessness simplifies scaling and request routing between replicas. If microservices maintain an internal state, every replica needs to be synchronised to achieve the desired load balancing with minimal risk of race conditions. While some level of stickiness in request routing will still be needed in stateless services, they will not have the complexity and overheads of state synchronisation across replicas.

Service granularity may need to be balanced with operational overheads and overall system complexity due to increasing number of services.

Increasing unit capacity through system efficiencies

Once the desired granularity has been determined, the unit capacity of each microservice, and that of the overall system, needs to be optimised so that they are able to process the optimum load for a given footprint. Beyond that optimum load, only the microservices that reach a predefined processing threshold scale horizontally.

Optimum unit capacity depends on computational, storage and communication efficiencies. Computational efficiencies require using appropriate data structures and algorithms that reduce the CPU and memory usage for a given load, or conversely, increase the processing capacity for a given CPU and memory footprint.

There is a common tendency in monolithic and legacy systems to enrich the data upfront. If this practice is continued in domain driven microservices based systems, these enrichments are replicated across domains, substantially increasing the storage footprint and the risk of inconsistencies. Assurance against the latter is achieved through reconciliations multiple times during the day to ensure that replicated data is consistent across domains. This leads to higher storage and computation spend. Ideally, each domain should store the data specific to the domain with just enough additional data to cross reference across other relevant domains. Enrichments can then be deferred to just prior to consuming data for reporting or displaying to consumers.

Upfront enrichment also increases the size of messages exchanged between microservices. These messages usually are encoded in JSON which further increases their footprint leading to higher serialisation and deserialisation overheads within microservices. This reduces the unit capacity of individual microservices. The common belief here is that fully enriched messages based on the overall canonical model will increase the ability to diagnose and troubleshoot issues in the system. Instead, they increase the processing overheads and create tighter design and implementation coupling between systems.

Canonical models should facilitate integration between systems with minimal possible communication overheads and provide the ability to the domains to further enrich data when required. This requires the model to make only these fields and entities mandatory that enable integration across domains and subsequent enrichment. Further, binary formats may be preferred over text based formats as the former are far more compact. This will also require means that maintain the same level of diagnostic and troubleshooting ability provided by text formats.

Achieving these efficiencies requires carefully building optimal domain models and regularly profiling and optimising individual microservices for performance, in addition to end-to-end performance and load testing. This requires engineering and product rigour from the very beginning in the product value stream, focused not just on functional aspects of the system but also the cross/non functional needs of the business.

Already on the cloud?

If you have already lifted and shifted to the cloud and costs are escalating beyond your expectations, the best way to get a handle on those is to incrementally decouple capabilities from your monolith. You need to prioritise those capabilities and sub-capabilities that tend to have higher and potentially varying load profiles. Optimising them for high unit capacity and low scale-out costs will not only start giving you a better control over your costs but will also enable you to determine the unit economics for the cloud consumption of your decoupled capabilities. This should equip you to have meaningful conversations with the business on how cloud costs vary with business volumes and potentially business revenues.

-

When Your Bank Goes Dark: The Regulatory Double Standard of Banking Availability

“If banks can’t offer something more valuable than Amazon Prime, then we’re probably in the wrong business”, Bradley Leimer

The banking availability paradox

𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐝𝐨 𝐫𝐞𝐠𝐮𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐬 𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰 𝐛𝐚𝐧𝐤𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐥𝐨𝐧𝐠 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐝𝐮𝐥𝐞𝐝 𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐨𝐰𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝟔 𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬 𝐨𝐫 𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐞? During these periods most of their critical services are unavailable. This is interesting especially when banks are mandated to recover from an unscheduled outage in less than 4 hours.

On 23rd March 2025, over 6 banks in Singapore had maintenance windows stretching to 6 hours or more in the early morning. At least 3 of them have regular weekend scheduled maintenance windows of such durations. 𝐓𝐚𝐥𝐤 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐮𝐩 𝐚𝐜𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐭, 𝐣𝐮𝐬𝐭 𝐢𝐧 𝐜𝐚𝐬𝐞 𝐲𝐨𝐮 𝐧𝐞𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐚 𝐩𝐚𝐲𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐟𝐞𝐫!

Banks may debate that their maintenance windows are during periods of reduced activity. But if they are offering digital services, they are promising 24×365 availability with global access.

𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐥𝐲 𝐝𝐮𝐞 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐫𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐨𝐬𝐭 𝐛𝐚𝐧𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐞𝐜𝐡 𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐬, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐚 𝐝𝐢𝐫𝐞 𝐧𝐞𝐞𝐝 𝐨𝐟 𝐝𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. This modernisation needs to include their practices and operating models. And it does not have to be disruptive to their business.

Last year, a similar “𝒎𝒂𝒊𝒏𝒕𝒆𝒏𝒂𝒏𝒄𝒆 𝒘𝒊𝒏𝒅𝒐𝒘” inconvenienced Amna, my wife. In a 15 minutes conversation narrated below, this digital banking user with no banking or technology background made a compelling strategic case for banking systems modernisation in plain speak.

A customer questions

My wife, Amna, is not a technical person and not familiar with practices in large banks and financial institutions. Still she had a very thought provoking conversation with me at breakfast one day.

Amna needed to transfer some money to our daughter, who is studying in the UK. In the morning, she tried using her UK bank’s (Acme for anonymity) mobile app for this and was disappointed on seeing a banner covering the app reading:

𝘞𝘦 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘳𝘰𝘶𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘦 𝘮𝘢𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘯𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘴𝘺𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘮𝘴 𝘴𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘱𝘱 𝘪𝘴 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘵𝘸𝘦𝘦𝘯 𝘮𝘪𝘥𝘯𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘵𝘰 6 𝘢𝘮 𝘰𝘯 4 𝘍𝘦𝘣𝘳𝘶𝘢𝘳𝘺 2024. 𝘞𝘦 𝘢𝘱𝘰𝘭𝘰𝘨𝘪𝘴𝘦 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘪𝘯𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘷𝘦𝘯𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘦.

This led to the following exchange between us:

Amna: What maintenance do they need on Acme’s banking app?

Me: They may need to add new features, fix existing defects, upgrade the hardware, networking, storage. It is not just the app that you see on the mobile, there is a lot of software running on the computers in their datacenters?

Amna: But why would they need six hours? I mean, it’s software isn’t it and aren’t they using computers. It’s not as if they are doing this manually with all those computers around them?

Me: Yes, ideally software should be changed with automation and even computers and networks can be configured automatically with little or no manual work. But then they have to test if the maintenance they have done has not broken anything else and everything works fine before they let their customers back into the system.

Amna: Again, why would they need hours for testing? Don’t tell me that they do that manually too. Can’t computers test themselves and other computers?

Me: Yes they can if they are programmed for it. All banks are different, some have more automation than others. I don’t know the state of Acme in this case.

Amna: Ok, but why then can they not have a spare set of computers and networks on which they can test to their heart’s content while their customers keep using the app on the other set of computers and networks. When they are happy with their testing, they can switch the customers to the new kit?

Me: (Almost speechless) Perhaps because it is very expensive to have spare kit lying around.

Amna: Can they not rent it?

Me: (Absolutely speechless – 𝐀𝐜𝐦𝐞, 𝐲𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝟲 𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐨𝐰 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐚𝐜𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐲𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐜𝐮𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐬!)

In less than 15 minutes, a digital banking customer not familiar with banking or technology has made a case for continuous delivery, testing automation, blue-green deployment and public cloud for banking. And she may not be the only one thinking all this.

Banks need to listen

Banks entered digital banking making promises of banking anywhere, anytime. Above is the voice of banks’ customers that they need to listen – denying them the 24×365 availability can be taken by the customers as a breach of promise, leading to erosion of trust. What will the banks do to prevent that?

-

Enhancing Ransomware Protection in Financial Services

Financial services are prime victims of ransomware. Attackers believe that they can demand higher ransoms from banks and financial institutions. It is not just because they have the capacity to pay large ransoms but also because the compromised information introduces substantial risk to their customers. The disruption to financial institutions can practically disrupt the lives and businesses of customers. The longer this disruption persists, more is the erosion of trust and confidence of customers and regulators, and higher is the reputational damage to the victims.

According to the 2023 Sophos survey of ransomware attacks on financial services, 64% firms suffered ransomware attacks, up from 55% in 2022. Only 14% of victims were able to stop the attacks before they were locked out. For over 25% of the attacks, the attackers stole and locked the data. 43% of the attacked financial institutions paid ransom to recover their data. On average they paid $1.6 million, up from nearly $275,000 the year before.

Banks and financial services are spending substantially to continuously improve their cyber security. Figures of 10% of their budgets or higher have been mentioned being spent on cyber security which, for many banks run into billions.

Regulators are also taking notice with new regulations like the EU’s Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) and APRA’s (Australian Prudential Regulation Authority) CPS-230. DORA mandates banks to follow the rules of operational resilience which includes the protection, detection, containment, recovery and repair capabilities against cyber incidents. The EBA (European Banking Authority) is also planning to run the first ever cyber resilience stress test to determine how banks would recover from a major cyber incident. With $3.5 trillion at stake just when the global payments systems are compromised, stakes cannot be much higher.

Their emphasis on recovery and repair has an important significance for ransomware protection. Many firms may be spending disproportionately less resources on their recoverability post a ransomware attack. In addition to building their security capabilities, they need to be equally focused on continuously improving their capability to swiftly recover from a ransomware attack.

Holistic ransomware protection and cyber resilience, therefore, needs to focus on the following four principles.

- Secure digital assets against cyber attacks

- Deny attackers any use of information stolen

- Restore systems quickly to minimise business disruption from a cyber attack

- Continuously improve security practices and tooling to reduce risk of future incidents

Cloud-nativity plays an important role in enhancing ransomware protection and cyber resilience.

Secure

Segmentation + Identity Security + Principle of least privilege

To understand what security should look like to prevent a ransomware attack, we need to understand how hackers get privileged access to systems. This means to be able to steal information and lock the owners of those systems out till they don’t pay ransom.

Such privileged access is only possible when hackers have access to root or superuser passwords. They use a range of methods like phishing or spear phishing attacks with emails that contain links clicking which will install malware on the victims’ computers. They are then able to monitor the activity on their victims’ computers to steal passwords and access codes. Many times, these passwords are stored on plain text files.

This highlights the importance of protecting identity and credentials. This also highlights the fragility of password only based authentication. If passwords are complemented with additional forms of authentication using trusted devices in possession of individuals authenticating, like MFA (Multi Factor Authentication) and passcodes, identity protection increases manifolds. Furthermore, access should only be granted based on the principle of least privilege, with audited and approved privilege escalation in exceptional circumstances.

Another serious security antipattern is the disproportionate emphasis on perimeter security. Perimeter security is important but is not the be all and end all of security. Zero trust security is ideal. Progressively securing assets behind the perimeter prioritised on risk helps incrementally achieve zero trust security.

Identity security and least privilege are the first important steps in achieving zero trust security. This should be complemented with segmentation. Production and non-production environments should be segmented appropriately followed by segmentation of subsystems and services so that if one environment, subsystem or service gets compromised, the attacker finds it challenging to laterally traverse to other environments.

Deny

Encryption + Segmentation + Risk based asset access control

Even with iron clad security, breaches happen. When this happens, it is quite possible that attackers will access the data they can get their hands on. And when that happens, ideally they should not be able to make use of that data.

Encrypting data at rest and in flight goes a long way in denying the hackers the use of stolen information. Furthermore, segmentation and risk-based asset security also helps deny attackers to move laterally from the breached system to others. This limits their ability to compromise and steal information from other subsystems and systems.

Encrypting data at rest can be very effective till the encryption keys or root/admin passwords are compromised. With those, hackers can decrypt and commercialise the stolen data.

Interestingly, enterprise architecture and domain driven design can also help limit hackers’ ability to meaningfully use the stolen data. If systems are compartmentalised into subsystems along domain boundaries and each of them owns their own data, relating stolen data from these stolen subsystems is all that much harder. Segregating data along domain boundaries also potentially enhances security as each of these domains can have separate credentials and secrets assigned to different domain owners. Compromising one domain does not necessarily mean that attackers have access to data of all other domains as well.

If all the enterprise or business data sits in one database with relational links across entities, it is a lot easier for hackers to, firstly, steal all the data once they access the database, and secondly link the entities together using relational links to make sense of all the customer activities and business details.

Restore

Secure backup (data and configuration) + Automated recoverability

Traditionally, system restoration has largely been the concern of operations, more recently of SRE (Site Reliability Engineering) and rarely of security. Even worse is that while firms fairly routinely perform DR (Disaster Recovery) tests, complete restoration from scratch is rarely practised, if ever.

This is where ransomware attackers are very effective. They lock their victims out of the compromised systems by encrypting data in and access to systems, taking control of identity registries and lock out admin or super user. Only if the system administrators could restore systems from scratch and then hydrate them with the backed up data and configuration, compromised businesses would not have to pay several millions in ransom to get access back to their systems and data.

Many firms choose not to pay the ransom and go through the exercise of painfully recovering their systems. Not only is this time consuming but substantially expensive, especially when considering the cost to the business because of a prolonged outage. There have also been reports of many of these businesses passing the cost of ransomware recovery to customers. Passing the costs of recovery to customers is adding insult to injury, when they are left all by themselves to defend against scams and fraud.

Most firms take their security seriously. So seriously in fact that they disproportionately spend on security at the cost of recoverability. Impregnable security is a myth. That does not mean that firms should not invest in it. In addition, firms should invest in swift recoverability of data and systems from scratch. This should also include measures that make the stolen data unusable.

Recoverability is also an increasing focus of emerging regulations. Again, regulations themselves may not be sufficient to protect customers. Also needed are credible measures of confidence demonstrated regularly, like recreating a new production environment from scratch and switching operations to it within the given lead time target (or the MTTR – mean time to recovery).

Continuously improve

Security shift left + Resilience testing + Monitoring + Patching + Evolving practices

The cybersecurity environment changes fast. Cyber risks are continuously evolving and systems need to be continuously assessed for new vulnerabilities which then need to be remediated. Furthermore, business also never stays static. Systems are continuously being modified, upgraded and maintained to meet evolving business needs. If due care is not exercised, vulnerabilities can easily creep into a system which was secure and resilient enough just recently.

Ensuring that a system maintains at least an acceptable level of protection requires a focus of the following:

- Shifting security left ensuring that security requirements are determined and fulfilled alongside functional requirements and tested automatically within delivery pipelines using techniques such as SAST (Static Application Security Testing) and DAST (Dynamic Application Security Testing).

- Performing regular pentesting and disaster recovery switchover drills. Drills that require recovering a system from scratch should also be planned and conducted. These would require installing the system on a brand new environment followed by hydrating it with data from secure backups.

- Monitoring system usage and behaviour in production and alerting on anomalous behaviour. This may require advanced analytic capabilities like machine learning to pick out micro trends in usage and behaviour which may remain undetected with static thresholds and manual observation.

- Monitoring industry and product advisories on new vulnerabilities, assessing each on the risk they pose to the business and prioritising their remediation.

- Continuously assessing inhouse security practices against the emerging industry trends and practices

Cloud nativity as an enabler

Whether your technology is on public cloud or on premises private cloud, a cloud native architecture and implementation along with automated provisioning, delivery and testing enables greater cyber resilience.

Modular, decoupled and domain driven architectures allow risk based prioritisation of security. Segregation along domain boundaries with access control reduces the risk of lateral threat movement. Data is also decoupled and aligned along domain boundaries making it more secure and providing opportunities to recover a system or its individual subsystems from scratch. Containerisation provides another layer of security if configured appropriately with further segregation at cluster and namespace levels. Automation techniques like Infrastructure as Code (IaC) provide traceability, consistency, repeatability and reversibility in infrastructure and platform configuration, attributes which are foundational for the continuous improvement of cyber resilience.

Further, public cloud providers have a shared responsibility model for security. They assume the responsibility of the security of the cloud which includes their infrastructure, virtualisation and host operating systems. They also ensure that services they provide have adequate and updated security features. Their configuration, however, is the responsibility of tenants. Tenants have the responsibility of their estate’s security in the cloud, which includes guest operating systems, application services, data and the configuration of cloud services they use. This relieves the tenants from substantial security heavy lifting that they would otherwise have to perform on premises.

-

Cloud Adoption – Speed vs Stickiness

Many firms are eager to reap the benefits of public cloud and want an accelerated cloud adoption. Many are apprehensive of the cost and risk of modernising and transforming their systems to cloud-native technology. They are lured into a lift-and-shift of their existing systems onto the public cloud with an expectation that transformation will be easier when they are on the public cloud.

The reality is that transformation post lift-and-shift is only marginally easier. Further, technology that is lifted and shifted, like-for-like, has proven to be more expensive to operate and maintain on the public cloud. The delay in realising the potential of public cloud and escalating costs have forced many firms to pause their cloud adoption and even repatriate some of their workloads back to their data centres.

They are also trying to negotiate more favourable usage contracts with cloud providers. Even if such contracts are agreed in favour of cloud customers, in the medium to long term, the inefficiencies of the technology will override this short term relief. This will force firms to reconsider their cloud adoption decisions later.

This raises the argument of speed vs stickiness of cloud adoption. Should firms rush to adopt cloud or should they target stickiness through transformation that helps achieve business outcomes?

More than the firms themselves, this is also a business strategy question for cloud providers. Should they focus on short term growth of cloud revenues through rapid cloud adoption or a more financially sustainable strategy that focuses on customer stickiness to the cloud?

Transformation is sticky – and it can be speedy

Modernisation and transformation of enterprise technology is expected to provide the desired benefits on public cloud, making it stickier on public cloud. But it is commonly perceived to be complex, costly and risky. To reduce the risk, firms proceed with the like-for-like approach and try to achieve full feature parity. Firms expect the same features supporting the same business processes as they migrate to the cloud. They expect that with feature parity, they are dealing with the known which would make cloud adoption faster and less risky.

There are quite a few misconceptions here. The first is that many of the features and business capabilities in the legacy or on-prem technology may no longer be in use. Some may no longer align with the existing business processes and are used with manual workarounds. Many of the capabilities implemented on-prem may be available off the shelf on public cloud. Last but not least, the infrastructure configuration for a lift and shift migration may not utilise many cloud native capabilities requiring a more involved or complex setup.

Taking all this into consideration, a lift and shift migration, though speedy, will eventually be costly and will offer less agility and poor flexibility on public cloud. Transformation and modernisation on the cloud will not be much simpler or faster than if it would have been attempted in the first place. This will eventually lead people to question their decision to adopt cloud in the first place.

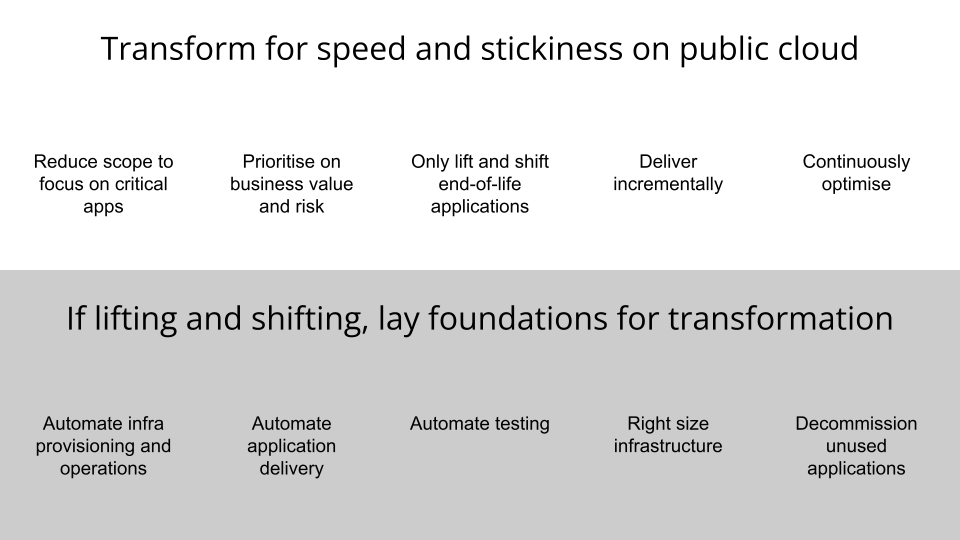

This then gives opportunities to make transformation speedy through:

- Reducing the scope of the initiative,

- Prioritising the transformation and migration of business capabilities based on risk and value,

- Lifting and shifting only the end of life applications,

- Delivering these capabilities incrementally into production on public cloud,

- Continuously optimising on the cloud to keep risk, cost and complexity low

Reducing the scope of initiative is crucial to reducing the risk and cost of the initiative and this involves:

- Decommissioning products, features and capabilities that provide diminishing returns or are no longer in use,

- Identifying the commodity and undifferentiated capabilities, and fulfilling them using off the shelf products and SaaS solutions,

- Utilising cloud native infrastructure and platform services to reduce the effort and scope of infrastructure provisioning and operations

These steps help strike a balance between speed and stickiness when transforming an on-prem estate to a cloud-native technology.

But if you have to lift and shift …

There may be reasons that necessitate a speedy lift and shift to the public cloud. A typical example is that of a stress data centre exit on a notice too short to migrate to an alternative data centre.

Here, a business may not have the time to consider transformation of their technology estate as part of migration. But if they decide that cloud is the ultimate destination, a lift and shift migration should only be seen as an initial step in the journey. Even for this initial step, they can take measures to ensure that eventual transformation starts on the right foot.

Some of these measures include:

- Automating infrastructure provisioning and management, ensuring consistency and repeatability across environments,

- Automating the delivery of applications on the infrastructure, increasing delivery efficiency,

- Automating testing, reducing the testing overhead and increasing testing confidence,

- Right-sizing the infrastructure based on usage statistics, optimising costs,

- Decommissioning applications that have little or no usage and are not providing any value, reducing the overall scope

These measures will help reduce delivery friction, increase delivery confidence, optimise costs and enhance operational efficiency when on public cloud. These will also motivate the business to consider cloud-native transformation of the technology to reap further benefits of the cloud, thus increasing stickiness while pursuing speed of cloud adoption.

In a nutshell …

When targeting cloud, speed and stickiness should not be an either-or decision. Businesses can strike a balance between both when pursuing such a strategic endeavour. They should look at realising the benefits cloud provides to maintain and extend their competitive advantage. That requires taking steps that ensure long term success on public cloud.

-

Change Management in Cloud-native Banking

Even well meaning gatekeepers slow innovation, Jeff Bezos

Resilient banking technology is essential to maintain and enhance trust and confidence in the financial system alongside ensuring business continuity for banks. Financial regulators have low tolerance for customer impacting failures of banking technology. Their scrutiny of such failures usually results in financial penalties for banks who may also have to compensate customers for losses and inconvenience. Altogether, this creates distractions that banks can ill afford when trying to compete in a dynamic and disruptive business environment.

It is, therefore, no surprise that technology governance and change management are critical for banks. In most banks, these have grown into substantial processes with multi-layered manual approvals. There is now credible evidence that such processes are slowing down delivering business and customer value. At the same time, these processes are not also enhancing confidence in technology change.

Traditional governance processes are also an obstacle in cloud adoption by banks. The friction they introduce restricts banks in achieving the benefits they desire from public cloud, such as business agility, economy and faster time to market. Hence, lifting and shifting traditional change management to cloud leads to suboptimal results. The question this blog post attempts to answer is, how banks may achieve the technology governance outcomes of regulatory compliance and low risk with much lower friction so they can capitalise on the benefits of adopting public cloud.

This blog proposes a platform strategy for banks where the building blocks of banking and regulatory compliance functionality are implemented as loosely coupled services of a platform. Change management and governance here is automated in the form of functional , cross functional and compliance tests that are specified and approved by the governance functions in the banks. All this together should lead to much lower friction, greater flexibility and higher efficiency resulting in increased agility and economy on public cloud.

Impact of Change Advisory Boards (CAB) and Orthodox Approvals

Banking Frameworks and Coupling

Decoupling through Digital Platforms

Automating Change Management and Compliance

The Evolving Role of CAB and Governance

Impact of Change Advisory Boards (CAB) and Orthodox Approvals

UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) conducted a change implementation survey in 2019 to ascertain the causes of significant IT failures in the preceding 10 years. The survey found substantial change activity in banks. In 2019 alone, an average of 35,000 average changes were implemented per firm. Out of the 1000 material incidents, 17% of the incidents were change related. Practices contributing to change failures included manual review and approvals.

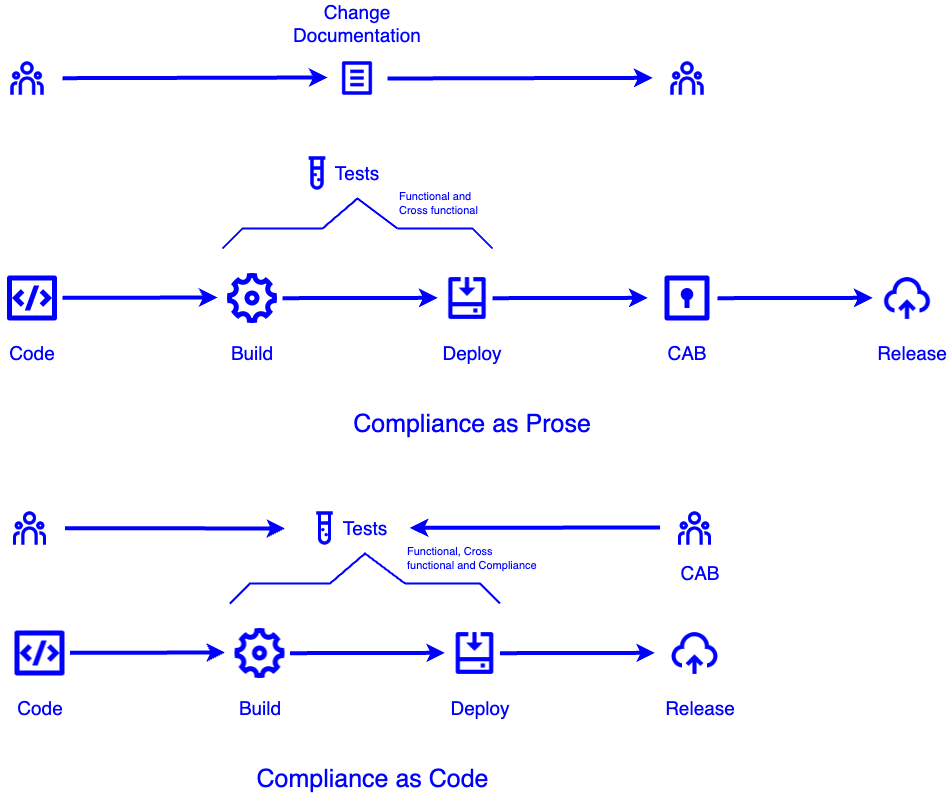

Most banks and financial institutions have Change Advisory Boards (CAB) to review and approve changes to production. CABs generally are formed of teams from technology, governance, risk and compliance. One major reason for constituting CABs is compliance with regulations around segregation of responsibilities, like Sarbanes Oxley (SOX). Banks consider that compliance with SOX requires people committing the change cannot approve and deploy it into production. There is a different interpretation of SOX that SOX does not mandate the manner in which approvals and change propagation should be implemented. All SOX requires is the person making the change is not the one reviewing it. By making changes small and self-contained, not only the complexity of the change is reduced, the reviews are far more comprehensive and effective.

As a result, CABs are far removed from the change itself. Change management and governance through CAB requires the teams to prepare lengthy and complicated change documentation, commonly referred to as compliance as prose. This introduces friction in change delivery without adding much confidence to change review and approvals. FCA found that CABs approved 90% of the changes they reviewed and in some firms CABs had not rejected a single change in 2019.

Hence, change management and oversight by CABs do not provide much confidence. At the same time they introduce friction in change delivery. These findings align with the findings revealed in the State of the DevOps Report (DORA) 2020 on change management in the wider industry. The report finds that firms with highly orthodox approvals are 9 times more inefficient than firms with low orthodox approvals.

Orthodox change management involves approvals by committees with multiple management layers and with rigid change schedules. Such governance and change management processes are orthogonal to cloud native operating models. Cloud native operating models benefit from end-to-end automation in delivery, including change management. These aim to progressively reduce friction while ensuring regulatory compliance and low risk.

Banking Frameworks and Coupling

Reduced friction from concept to cash automatically increases innovation opportunities. Banks are then able to implement ideas into production fast, measure the outcomes and adapt swiftly to maximise value to customers. At the same time, banks want to minimise risk of changes and ensure regulatory compliance. Traditionally, orthodox approvals have been used to ensure that risk remains low and regulations are complied with. As mentioned before, orthodox approvals generally fail to achieve these and at the same time restrict innovation opportunities by introducing more friction in the delivery process.

Banks have traditionally employed reuse to speed up delivery as well as ensure compliance. Key banking workflows are implemented as comprehensive frameworks which also provide functionality for regulatory compliance. The premise here is that application development teams using these frameworks get regulatory compliance functionality out of the box when they use these frameworks. Furthermore, with such frameworks, the change approval process was expected to simplify.

But reuse through large frameworks introduces coupling, not just between systems and the frameworks but also across different teams. Furthermore large, comprehensive frameworks are inherently complex which makes their own evolution slow and risky. All these factors add up to increase friction, not reduce it. Similarly, framework based banking systems require greater orthodox governance, not less.

Decoupling through Digital Platforms

Digital platforms are an alternative approach to frameworks. Platforms are composed of modular, decoupled and composable services that expose their capabilities via open and secure APIs. These services provide both business and regulatory capabilities. Business applications compose their workflows by orchestrating the relevant business and regulatory APIs as required.

Platforms introduce much less coupling than frameworks. Individual platform and application services can evolve independently. This allows breaking down changes into much smaller and less risky changes. Each of these granular changes require equally simpler yet more effective change management oversight as they are propagated to production.

The FCA survey mentioned above also revealed that major changes were twice as likely to result in an incident. While the firms appreciated the need to break changes down to reduce the risk, complexity of changes makes it difficult to decompose these changes. However big changes can be decomposed into smaller independent changes by decomposing the entire system into modular and decoupled services where each service can evolve independently. The overall system is then composed through the orchestration of these services.

Automating Change Management and Compliance

While digital platforms reduce friction by decoupling technology and teams, governance and compliance may be concerned whether the necessary regulatory services are being appropriately orchestrated. Orthodox change approvals with platforms can then tend to become more complicated, not less.

Traditional governance and compliance is achieved via prose, i.e., written instructions and checklists, that need to confirm compliance, are manually followed for each change. This makes governance and compliance laborious and error prone. Manual compliance checks are largely performed far to the right of the development cycle, usually before release to production. This makes changes to achieve compliance more disruptive and expensive. As mentioned above, the volume of change in financial institutions is considerably large. Mistakes are highly likely and, as the FCA survey suggests, they can lead to client impacting issues in production.

The alternative is to implement compliance as code. Here all the compliance and regulatory checks are implemented as automated tests. These tests are specified by governance functions like CAB and are implemented by developers. Once integrated with the CI/CD (Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment) pipelines, every change is automatically tested for compliance as it is committed to the source control and progressed through the deployment pipelines. Compliance is tested to the left of the development cycle with fast feedback directly to the developers as results of failed tests.

CAB then no longer needs to manually confirm every change for compliance. This significantly reduces

- friction in delivering the change to production,

- risk of propagating non-compliant changes,

- effort in confirming compliance.

The DORA 2020 report suggests that involving engineering teams in governance and change management leads to 5 times more effectiveness through a shared understanding of the outcomes and process. As a result employees report higher involvement and are 13% more likely to understand and enjoy the process.

The Evolving Role of CAB and Governance

Some may argue the need for CAB and governance with compliance as code. Both CAB and governance are still needed but their roles evolve from prescriptive, output focused and activity based to outcome driven and principles aligned. Governance functions, including CAB, specify to engineering the outcomes they want achieved. Engineering and governance can then collaboratively convert those outcomes to automated tests which are integrated into development and delivery automation for early and frequent feedback on compliance. Any changes to the compliance tests need to be approved by governance. However, governance need not intervene in the delivery when all the specified tests are passing.

In many ways, the role of CAB and governance is elevated. They no longer need to ensure that compliance is achieved. They delegate this to the engineering teams and advise them on how compliance may be confirmed using automated tests. Beyond that, they focus on understanding the emerging regulatory requirements and their impact on business. They also assess how existing regulatory requirements can be ensured for new business capabilities.

Conclusions

Governance and compliance is essential to ensure confidence in technology used in regulated businesses like banking and finance. However, traditional governance processes with orthodox multilayered approvals introduce substantial friction in delivering technology to drive business value. And it has not shown any reduction in risk. Furthermore, lifting and shifting these processes to public cloud restricts the agility and economy public cloud can provide to businesses.

Automating compliance as code and changing the role of CABs from gatekeepers to advisors increases the involvement of teams in ensuring compliance early in the development process. This leads to faster feedback in case of non-compliance and at the same time reduces both friction and risk in delivering change. On public cloud, this translates to increased agility, greater economy and faster speed to market.

-

Concentration Risk of Banking on Public Cloud

Public cloud adoption in banks and financial institutions is increasing, especially since the beginning of the pandemic, when the public had to rely on digital banking and contactless payments. Further, higher COVID related volatility in capital markets led to unprecedented trading volumes prompting capital markets firms and trading venues to seriously consider public cloud (e.g., Nasdaq plans to move all its 28 markets to public cloud by 2030). In a research conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) in 2021, 72% of banking IT executives surveyed believed that cloud will help their organisations achieve their business objectives and over 80% of them had a clear cloud adoption strategy.

Also increasing is the concern among financial industry regulators globally on what they see as increasing levels of outsourcing of banking technology to a few public cloud providers. The risk due to such dependence is referred to as concentration risk and most regulators are now considering this as a major risk to the stability of regional and global financial systems.

At least for now, financial regulators are demonstrating a more balanced, mature and an outcome driven approach to managing this risk. This is primarily because of the opportunities for competition, innovation and financial inclusion public cloud offers. The situation, however, may evolve as the dependence on public cloud and the corresponding risk grows, requiring further oversight of not just the banks but also of cloud service providers.

This blog discusses the key concerns financial regulators have around concentration risk, how this risk may be mitigated and what the future looks like for banking on public cloud from a regulatory perspective.

- Why are the regulators worried?

- What do the regulators want banks to do?

- How can banks mitigate concentration risk?

- What can the industry expect?

- Conclusions

Why are the regulators worried?

Traditional concerns of regulators around security and resilience have largely been addressed. Public cloud, with its shared responsibility model, is largely considered more secure than on-premises infrastructure while a widespread public cloud footprint offers opportunities for greater resilience. Regulators are now turning their attention to concentration risk and transparency in the operations of cloud service providers.

Concentration risk arises when a bank or a financial institution hosts all of its material business services on a public cloud offering. This risk also arises when a large number of banks and financial institutions host their material business services on a limited number of public cloud offerings. Business services are considered material if their failure or disruption result in a systemic impact on a bank individually or on the entire financial system.

Concentration risk has consequences far beyond just the resilience of cloud infrastructure. Following three scenarios alone are enough to keep regulators on the edge. Each of these cases can lead to severe disruption to banking and finance if banks are locked in with a particular cloud provider and do not have sufficient capability or capacity in-house to run their material services off public cloud,

- Big tech makes decisions that disadvantage banks. Cloud service providers may make commercial, technical and logistical decisions that may not favour banking and finance. Banking and finance is just one industry vertical utilising cloud services, not necessarily the largest in terms of revenues for cloud providers.

- Big tech thinks it is too big to fail. Cloud service providers may experience the Lehman moment where they think they are too big to fail and take risks that lead to their insolvency causing disruption to all their customers, including banks. What makes it worse is that banking is a common service for all other industries that is used practically in every business transaction no matter how big or small.

- Geopolitical risks. All large cloud providers are headquartered in the United States except Alibaba, which is headquartered in China. In case these governments pass legislations that do not align with the regulatory requirements in other jurisdictions, it may lead to geopolitical consequences.

If any such scenarios occur, regulators fear a stressed exit of banks from the public cloud. Without the preparation for a stressed exit, banks risk serious disruption to their material services which will result in loss of confidence in the regional and global financial systems.

What do the regulators want banks to do?

For the regulators, banks outsourcing hosting of their services to public cloud does not mean that they can outsource the responsibility and accountability for the uninterrupted operations of their services on the cloud. Banks need to demonstrate that they will be able to ensure business continuity in case they have to perform a stressed exit from their public cloud provider in case of a catastrophic event. This is in addition to them fulfilling on public cloud all the regulatory requirements, especially those related to security, resilience and data residency.

Banking’s public cloud adoption has been successful when regulators have avoided being prescriptive to the banks on how to fulfill regulatory requirements on public cloud. Here as well, regulators should avoid being prescriptive about how banks may mitigate the cloud concentration risk. This requires defining measures of success for the banks to demonstrate that they have successfully mitigated the cloud concentration risk. These may include stressed exit exercises that banks have to execute to demonstrate confidence in their strategies.

How can banks mitigate concentration risk?

Most banks adopting a public cloud strategy are looking at cloud portability across private, hybrid and multiple clouds. Traditionally, this has been controversial because of the costs involved and the apprehension that applications may not be able to fully utilise the capabilities a cloud platform provides especially when pursuing multi-cloud. However, cloud portability is the only viable approach currently to mitigate cloud concentration risk. The EIU research mentioned above suggests that over 80% of the banking IT executives think that multi-cloud will become a regulatory prerequisite for cloud adoption of banks.

Banks may want to invest in a platform that abstracts cloud native capabilities from the applications that consume them and the long-lived evolution and governance of the platform as a product. Cloud portability then impacts just the platform and not the applications that consume them. This may also not be easy or straight forward. But, this investment will provide a unified approach to applications to consume common business agnostic cloud capabilities. Business application development teams can then also focus on application specific and business differentiating capabilities and features.

Where application development teams do need to consume cloud capabilities not currently in the platform, they should adopt architecture techniques such as hexagonal architecture to provide similar levels of decoupling. At the same time, application development teams should engage with their technology governance function and platform teams to discuss assimilating these capabilities into the platform in the future.

Data egress from the public cloud has often been referred to as the key obstacle to cloud portability. Most public cloud providers charge for data egress and the cost of moving data out in case of a stressed exit can become exorbitant for cloud native banks. Banks can approach this challenge in the following ways:

- Negotiate: Banks can negotiate with their cloud provider that data egress for business continuity should not be charged or should be charged at a lower rate.

- Reduce: Banks should highlight the information that they critically need for regulatory, operational and business continuity purposes so only that may be considered for egress. They may also consider compaction and compression to further reduce egress costs.

- Increment: Periodically and incrementally backing up their data either on-premises or to a different cloud provider may make egress more affordable and further enhance business continuity.

What can the industry expect?

Regulators are moving ahead to bring regulatory oversight on cloud providers and big tech to ensure the resilience of financial services. The European Commission has published the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) and UK regulators are hinting at regulatory oversight on public cloud providers. How successful the regulators will be is still to be seen as the big tech will challenge the jurisdiction of foreign regulators. Furthermore, historically, big tech has considered regulation as stifling innovation.

Big tech may have to collaborate with regulators in complying with these regulations rather than confronting them, just as the banks have for adopting public cloud. At the same time, banks and financial institutions may require public cloud providers to standardise the complaint consumption of cloud capabilities. The European Cloud User Coalition (ECUC) is a coalition of European banks that is jointly agreeing on the requirements for compliant public cloud usage by financial institutions in the EU. Together, the banks, cloud providers and regulators should develop outcome driven approaches to minimise concentration risk and ensure regulatory compliance.

We may also see unbundling of public cloud for financial services so cloud providers can focus and limit regulatory scrutiny while still being able to innovate. Some may point to previous failed attempts by the regulators to break up big tech firms, however, those were largely focused on anti-trust as opposed to concerns on achieving very specific outcomes. We may start seeing the emergence of public cloud offerings just for financial services from the existing cloud providers, like the IBM Cloud for Financial Services. These may be easier to regulate in the future while isolating the rest of the firm from the impact of regulatory oversight.

Conclusions

The role of public cloud in increasing competition and innovation in banking is undeniable, which has led to greater financial inclusion. Regulators’ concerns on concentration and resilience are also justified and need to be addressed. It is in the interest of banks, cloud providers and regulators to work together in achieving the outcomes of the regulations rather than being prescriptive about them. Innovation and compliance do not have to be in tension with one another.