Scale-out costs

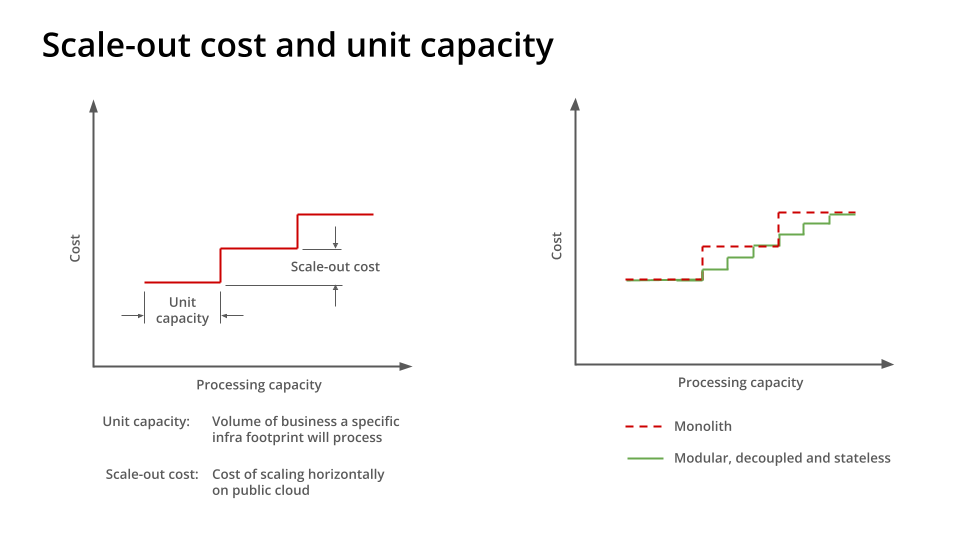

The costs incurred when scaling horizontally on a public cloud are referred to as scale-out costs. The more granular this scaling is, the lower are scale-out costs, giving firms higher margins when operating on public cloud.

Scale-out costs go hand in hand with a system’s unit capacity, i.e., the volume of business activity a particular infrastructure footprint will process before additional capacity needs to be provisioned to accommodate further volumes.

The knowledge of unit capacity and scale-out costs also help build rich unit economics models that enable technology to have meaningful cost conversations with the business in the context of business volumes and revenues. They also enable the technology to determine and optimise cost hotspots, i.e., the services where cost variations do not favourably align with business load variations.

Horizontal scaling on an elastic infrastructure was a key cost reduction measure that hyperscalars promised when promoting public cloud. Many argue that the manner in which public cloud adoption was pushed, with rushed migrations, firms were not given a chance to optimise for horizontal scaling and leverage granular scale-out costs. This has led to a perception of unfulfilled promises.

With this knowledge, what do we need to do minimise scale-out costs and increase the public cloud’s viability for businesses with rapidly and widely varying business activity.

In a nutshell,

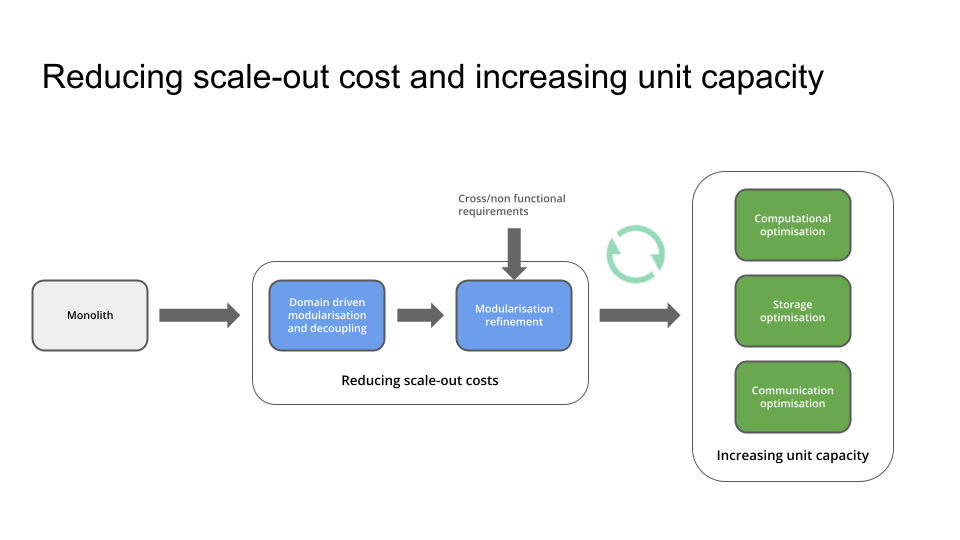

- it starts with modularising and decoupling a monolith along domain boundaries,

- further refining the granularity to meet specific scaling and performance requirements,

- optimising services for computational, storage and communication efficiencies,

- and continuously monitoring and optimising services to efficiently and economically scale according to business needs.

The cloud cost betrayal

One of public cloud’s big promises was cost reduction. But for most businesses adopting cloud, that has not happened. In fact, for many businesses, costs escalated to levels that forced them to repatriate some or all of their workloads back on-premises. Some reports suggest that if the AI workloads are discounted from hyperscalers’ revenues, their growth has declined to alarming levels.

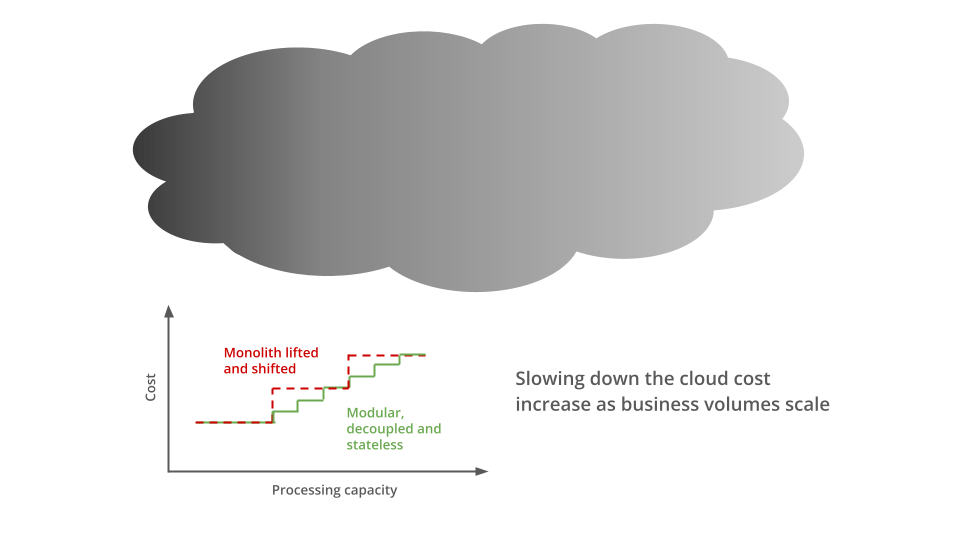

One of the key reasons for high cloud costs was lifting and shifting on-premises applications to cloud without modularising, decoupling and optimising them. These applications over provision infrastructure footprints on cloud similar to that in the data centers. As infrastructure unit costs in public cloud are considerably higher than on premises, this leads to substantially higher operating costs in public cloud.

One other promise the public cloud makes is that of elastic capacity. This means that if an application on a public cloud experiences higher utilisation then it can be horizontally scaled (or scaled out) to balance the load and avoid impacting system performance and customer experience. Once the load on the application returns to normal, the application scales back in.

If an application is a monolith, coarsely modular or tightly coupled, it consumes greater incremental resources when scaling out, leading to higher scale-out costs. This is because the entire estate may need to be scaled out for higher loads. But if an application is composed of modular and decoupled services, only the services experiencing bottlenecks because of increased load scale out, thus reducing the scale-out cost for the application.

Granularity – reducing scale-out costs

Modularity is just not enough to make scale-out costs granular. Only when modular services are decoupled and stateless, bottlenecked services can be scaled out independently thus reducing the scale-out costs.

A typical approach to achieving modularity and decoupling starts with identifying domain boundaries. The monolith can then be split along those domain boundaries into bounded contexts of one or more microservices. Further decomposition may be necessary to achieve specific cross/non functional requirements. For instance, if read and write loads on a particular microservice are asymmetric, that microservice may further be decomposed using the CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation) pattern. Such approaches may further reduce scale-out costs.

Statelessness simplifies scaling and request routing between replicas. If microservices maintain an internal state, every replica needs to be synchronised to achieve the desired load balancing with minimal risk of race conditions. While some level of stickiness in request routing will still be needed in stateless services, they will not have the complexity and overheads of state synchronisation across replicas.

Service granularity may need to be balanced with operational overheads and overall system complexity due to increasing number of services.

Increasing unit capacity through system efficiencies

Once the desired granularity has been determined, the unit capacity of each microservice, and that of the overall system, needs to be optimised so that they are able to process the optimum load for a given footprint. Beyond that optimum load, only the microservices that reach a predefined processing threshold scale horizontally.

Optimum unit capacity depends on computational, storage and communication efficiencies. Computational efficiencies require using appropriate data structures and algorithms that reduce the CPU and memory usage for a given load, or conversely, increase the processing capacity for a given CPU and memory footprint.

There is a common tendency in monolithic and legacy systems to enrich the data upfront. If this practice is continued in domain driven microservices based systems, these enrichments are replicated across domains, substantially increasing the storage footprint and the risk of inconsistencies. Assurance against the latter is achieved through reconciliations multiple times during the day to ensure that replicated data is consistent across domains. This leads to higher storage and computation spend. Ideally, each domain should store the data specific to the domain with just enough additional data to cross reference across other relevant domains. Enrichments can then be deferred to just prior to consuming data for reporting or displaying to consumers.

Upfront enrichment also increases the size of messages exchanged between microservices. These messages usually are encoded in JSON which further increases their footprint leading to higher serialisation and deserialisation overheads within microservices. This reduces the unit capacity of individual microservices. The common belief here is that fully enriched messages based on the overall canonical model will increase the ability to diagnose and troubleshoot issues in the system. Instead, they increase the processing overheads and create tighter design and implementation coupling between systems.

Canonical models should facilitate integration between systems with minimal possible communication overheads and provide the ability to the domains to further enrich data when required. This requires the model to make only these fields and entities mandatory that enable integration across domains and subsequent enrichment. Further, binary formats may be preferred over text based formats as the former are far more compact. This will also require means that maintain the same level of diagnostic and troubleshooting ability provided by text formats.

Achieving these efficiencies requires carefully building optimal domain models and regularly profiling and optimising individual microservices for performance, in addition to end-to-end performance and load testing. This requires engineering and product rigour from the very beginning in the product value stream, focused not just on functional aspects of the system but also the cross/non functional needs of the business.

Already on the cloud?

If you have already lifted and shifted to the cloud and costs are escalating beyond your expectations, the best way to get a handle on those is to incrementally decouple capabilities from your monolith. You need to prioritise those capabilities and sub-capabilities that tend to have higher and potentially varying load profiles. Optimising them for high unit capacity and low scale-out costs will not only start giving you a better control over your costs but will also enable you to determine the unit economics for the cloud consumption of your decoupled capabilities. This should equip you to have meaningful conversations with the business on how cloud costs vary with business volumes and potentially business revenues.

2 responses to “Scale out or sell out – How to tame your raging cloud bill”

[…] Scale out or sell out – How to tame your raging cloud bill […]

LikeLike

[…] for your applications will also increase, leading to higher costs. The challenge is how to keep the scale-up costs low and incremental. If these applications are monolithic and tightly coupled, scale-up costs can be high with […]

LikeLike